Nested cross-validation#

Cross-validation can be used both for hyperparameter tuning and for estimating the generalization performance of a model. However, using it for both purposes at the same time is problematic, as the resulting evaluation can underestimate some overfitting that results from the hyperparameter tuning procedure itself.

Philosophically, hyperparameter tuning is a form of machine learning itself and therefore, we need another outer loop of cross-validation to properly evaluate the generalization performance of the full modeling procedure.

This notebook highlights nested cross-validation and its impact on the estimated generalization performance compared to naively using a single level of cross-validation, both for hyperparameter tuning and evaluation of the generalization performance.

We will illustrate this difference using the breast cancer dataset.

from sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer

data, target = load_breast_cancer(return_X_y=True)

First, we use GridSearchCV to find the best parameters via cross-validation

on a minimal parameter grid.

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

from sklearn.svm import SVC

param_grid = {"C": [0.1, 1, 10], "gamma": [0.01, 0.1]}

model_to_tune = SVC()

search = GridSearchCV(estimator=model_to_tune, param_grid=param_grid, n_jobs=2)

search.fit(data, target)

GridSearchCV(estimator=SVC(), n_jobs=2,

param_grid={'C': [0.1, 1, 10], 'gamma': [0.01, 0.1]})In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook. On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

GridSearchCV(estimator=SVC(), n_jobs=2,

param_grid={'C': [0.1, 1, 10], 'gamma': [0.01, 0.1]})SVC(C=0.1, gamma=0.01)

SVC(C=0.1, gamma=0.01)

We recall that, internally, GridSearchCV trains several models for each on

sub-sampled training sets and evaluate each of them on the matching testing

sets using cross-validation. This evaluation procedure is controlled via using

the cv parameter. The procedure is then repeated for all possible

combinations of parameters given in param_grid.

The attribute best_params_ gives us the best set of parameters that maximize

the mean score on the internal test sets.

print(f"The best parameters found are: {search.best_params_}")

The best parameters found are: {'C': 0.1, 'gamma': 0.01}

We can also show the mean score obtained by using the parameters best_params_.

print(f"The mean CV score of the best model is: {search.best_score_:.3f}")

The mean CV score of the best model is: 0.627

At this stage, one should be extremely careful using this score. The misinterpretation would be the following: since this mean score was computed using cross-validation test sets, we could use it to assess the generalization performance of the model trained with the best hyper-parameters.

However, we should not forget that we used this score to pick-up the best model. It means that we used knowledge from the test sets (i.e. test scores) to select the hyper-parameter of the model it-self.

Thus, this mean score is not a fair estimate of our testing error. Indeed, it can be too optimistic, in particular when running a parameter search on a large grid with many hyper-parameters and many possible values per hyper-parameter. A way to avoid this pitfall is to use a “nested” cross-validation.

In the following, we will use an inner cross-validation corresponding to the previous procedure above to only optimize the hyperparameters. We will also embed this tuning procedure within an outer cross-validation, which is dedicated to estimate the testing error of our tuned model.

In this case, our inner cross-validation always gets the training set of the outer cross-validation, making it possible to always compute the final testing scores on completely independent sets of samples.

Let us do this in one go as follows:

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score, KFold

# Declare the inner and outer cross-validation strategies

inner_cv = KFold(n_splits=5, shuffle=True, random_state=0)

outer_cv = KFold(n_splits=3, shuffle=True, random_state=0)

# Inner cross-validation for parameter search

model = GridSearchCV(

estimator=model_to_tune, param_grid=param_grid, cv=inner_cv, n_jobs=2

)

# Outer cross-validation to compute the testing score

test_score = cross_val_score(model, data, target, cv=outer_cv, n_jobs=2)

print(

"The mean score using nested cross-validation is: "

f"{test_score.mean():.3f} ± {test_score.std():.3f}"

)

The mean score using nested cross-validation is: 0.627 ± 0.014

The reported score is more trustworthy and should be close to production’s expected generalization performance. Note that in this case, the two score values are very close for this first trial.

We would like to better assess the difference between the nested and non-nested cross-validation scores to show that the latter can be too optimistic in practice. To do this, we repeat the experiment several times and shuffle the data differently to ensure that our conclusion does not depend on a particular resampling of the data.

test_score_not_nested = []

test_score_nested = []

N_TRIALS = 20

for i in range(N_TRIALS):

# For each trial, we use cross-validation splits on independently

# randomly shuffled data by passing distinct values to the random_state

# parameter.

inner_cv = KFold(n_splits=5, shuffle=True, random_state=i)

outer_cv = KFold(n_splits=3, shuffle=True, random_state=i)

# Non_nested parameter search and scoring

model = GridSearchCV(

estimator=model_to_tune, param_grid=param_grid, cv=inner_cv, n_jobs=2

)

model.fit(data, target)

test_score_not_nested.append(model.best_score_)

# Nested CV with parameter optimization

test_score = cross_val_score(model, data, target, cv=outer_cv, n_jobs=2)

test_score_nested.append(test_score.mean())

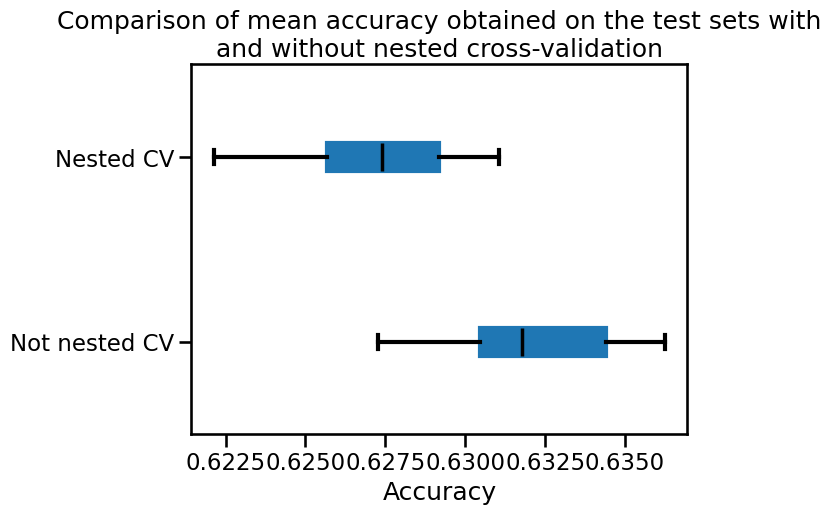

We can merge the data together and make a box plot of the two strategies.

import pandas as pd

all_scores = {

"Not nested CV": test_score_not_nested,

"Nested CV": test_score_nested,

}

all_scores = pd.DataFrame(all_scores)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

color = {"whiskers": "black", "medians": "black", "caps": "black"}

all_scores.plot.box(color=color, vert=False)

plt.xlabel("Accuracy")

_ = plt.title(

"Comparison of mean accuracy obtained on the test sets with\n"

"and without nested cross-validation"

)

We observe that the generalization performance estimated without using nested CV is higher than what we obtain with nested CV. The reason is that the tuning procedure itself selects the model with the highest inner CV score. If there are many hyper-parameter combinations and if the inner CV scores have comparatively large standard deviations, taking the maximum value can lure the naive data scientist into over-estimating the true generalization performance of the result of the full learning procedure. By using an outer cross-validation procedure one gets a more trustworthy estimate of the generalization performance of the full learning procedure, including the effect of tuning the hyperparameters.

As a conclusion, when optimizing parts of the machine learning pipeline (e.g. hyperparameter, transform, etc.), one needs to use nested cross-validation to evaluate the generalization performance of the predictive model. Otherwise, the results obtained without nested cross-validation are often overly optimistic.